Tales of the Ring

What do the names “Red” Moffett, “Iceman” John Scully, Billy Warburton, Edward Tuohey, Horatio Bolster, and Reddy the Blacksmith have in common? They all have ties to the pugilistic history of Milford.

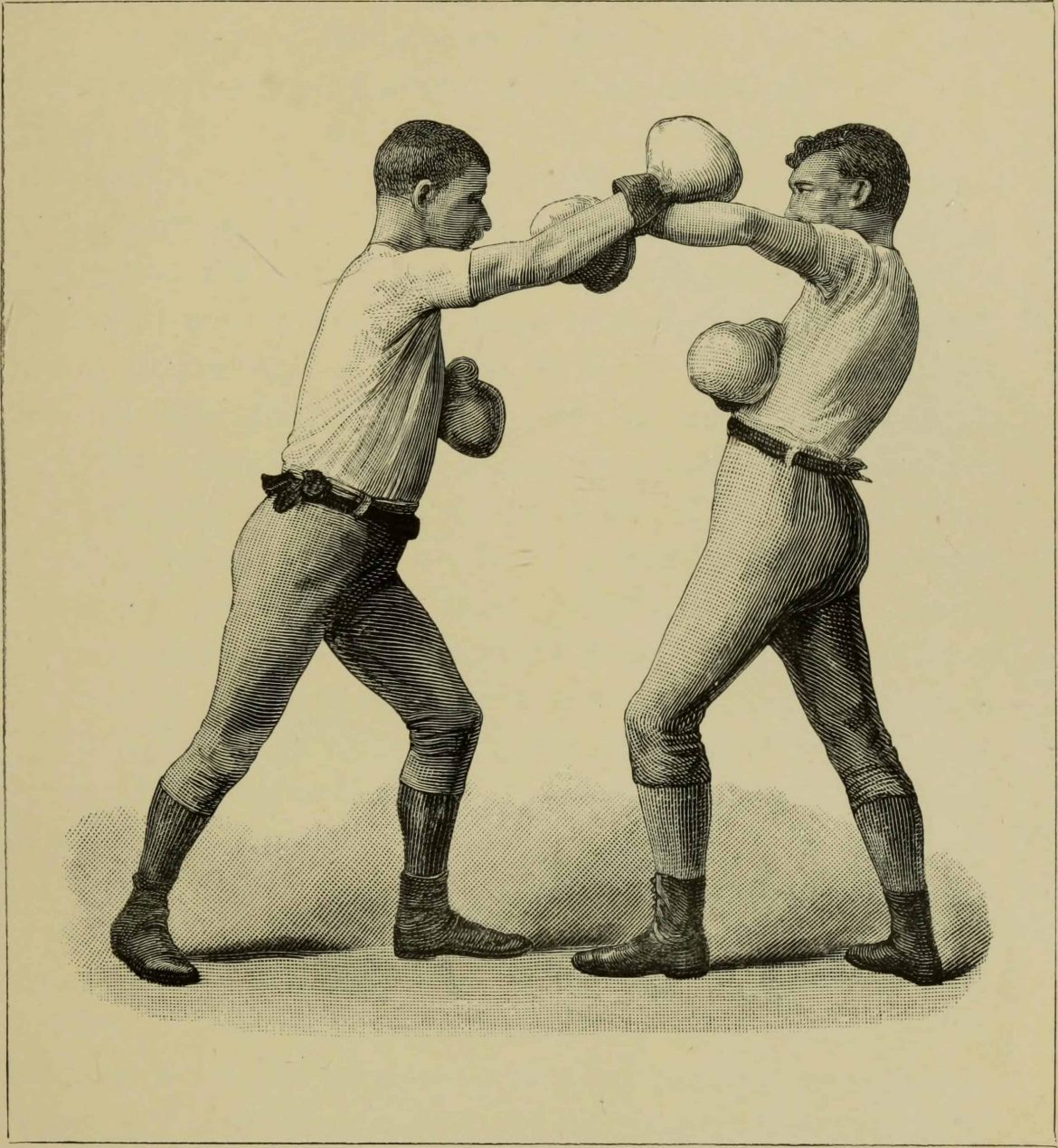

For a small, quiet New England town, Milford has hosted some epic demonstrations of the sweet science. While some of these fisticuffs have happened legitimately in the ring, the Marquess of Queensbury rules were not always strictly followed, and on at least one occasion, group participation led to a John Wayne-esque, Quiet Man-style Donnybrook breaking out in the streets of Milford.

Boxing had been a popular sport in the United Kingdom throughout the 1700s, but it wasn’t until an influx of immigrants during the 1800s that the sport began to dominate in America. With the rising population in cities, boxing became extremely popular and was looked at as a way for poor, unskilled immigrants to earn money. The only problem of course, was that boxing was illegal in most locations.

Associated with all sorts of crime, the gambling, drinking, and general lawlessness that surrounded the sport of boxing led to prize fights being cracked down on by city governments and police departments. One way around this barrier was to host clandestine bouts outside the watchful eyes of constables and detectives. Where better for gang members and hooligans from New York’s notorious Five Points neighborhood to organize prize fights than sleepy little Milford, Connecticut.

On February 11, 1867, a large group of men associated with The Bowery Boys, a New York gang famous for anti-Catholic violence, gang warfare, and rigging elections, boarded a train bound for New Haven. Once onboard, they met up with their boxer, Billy Warburton, and, according to a New York Herald reporter who was present, proceeded with a retinue of “Yale students, gamblers, thieves, and pickpockets to a makeshift ring set up on the banks of the Housatonic River.” At 9:00 a.m. the next morning, Warburton threw his hat in the ring to signify his intention to fight. At 10:00 a.m., as the crowd grew larger, his challenger Horatio Bolster, threw his hat in as well. Bolster, the smaller of the two fighters, employed a sort of rope-a-dope defense made famous by Muhammad Ali. Bolster would take a few punches and then flop, smiling, to the mat. After a few rounds of this, Warburton became frustrated. In the 6th round, Bolster flopped again, and an angry Warburton followed him to the mat landing punches on the prone fighter. Punching a man while down was one of the few prohibitions in 19th century boxing, and Warburton was disqualified.

The enraged crowd made its way back through Milford where fights broke out, windows and fences were smashed, and general mayhem ensued. At the Milford train depot an impromptu fight was arranged. The New York Tribune reporter at the scene wrote, “They fought up and down the enclosed track in the most disgusting and beastly manner for a space of twenty minutes…without interference from the delighted crowd…while three country police stood at a distance of about 20-feet calmly whittling sticks…”

After the fight at the train depot and the damage done to the town, newspapers called for investigations and an increased police force. After another prize fight in Mystic in 1869 where the Bowery Boys took control and robbed a train full of passengers on their return home, the state of Connecticut had had enough.

In 1870, a New York criminal named Reddy the Blacksmith organized a fight between Edward Touhey and James Kerrigan to be fought on Charles Island in Milford. This time, Connecticut’s Governor Marshall Jewell was ready. Word of the fight reached the police and Jewell called in the National Guard. Kerrigan and Reddy were arrested in Bridgeport, fans were arrested on Charles Island, and train loads of fight fans were arrested in Fairfield and Bridgeport before they ever made it to town.

As word got out that the fight was canceled, more violence broke out as unruly fight fans returned to Milford. According to the History of Milford, 1639-1939, “The county sheriff decided on immediate action. A special train at New Haven depot was loaded with five militia companies…and dispatched to Milford…. Nearly two hundred armed men departed for the scene of the combat. Governor Jewell ordered the sheriff and his men to arrest every possible violator of the law in an effort to stamp out prize fighting in Connecticut… after a flurry of combat, the crowd surrendered…” When word got out that Reddy the Blacksmith and his retinue were in jail, the New York Sun reportedly ran the headline “Keep them Connecticut.’”

As time passed, boxing became more accepted and less likely to cause riots. Boxing advocates, including Theodore Roosevelt, pushed the theory of “muscular Christianity,” believing boxing increased physical and moral health. Schools, churches, and local gyms all promoted boxing as a healthy choice, and local arenas began to put on fights. The New Haven Arena, The White City Stadium at Savin Rock, the Mosque in Bridgeport, and the Walnut Beach Stadium in Milford all regularly promoted prize fights.

One Milford resident who laced up the gloves professionally was Alfred “Red” Moffett. Also known as “The Devon Fireball,” Moffett was the junior welterweight boxing champion of Connecticut. He started his career in 1936 when he was 16 and boxed professionally for 10 years, interrupted by a stint in the Navy during WWII. After his career in the ring ended, he became a local police officer and taught boxing for the Police Athletic League (PAL). Before his passing in 2005 Red wrote in Sand in Our Shoes, “An event that took place on August 29, 1941 billed me as “Red Moffett, the Devon Irishman”. …Twelve hundred people attended the fight. I wasn’t the favorite to win…but I won the fight by decision. I will always remember those days when boxing at the Walnut Beach Stadium drew huge crowds of fans…”

Those old venues no longer exist, and with the rise of Mohegan Sun and Foxwoods casinos, professional boxing in Connecticut has moved east. In 1992, Milford hosted its last big fight when Connecticut’s Super Middleweight “Iceman “John Scully defeated Herman Farrar by TKO in three rounds.

When asked if he thought boxing was a dying sport, local boxing historian Jack Monroe throws this rhetorical punch: “How can you afford to give fighters $57 million if it’s dying?” From local boxing gyms, to casinos and pay per view, boxing can still bring out a crowd.

Just don’t smash any windows.