…He was a native of Connecticut, a State which supplies the Union with pioneers for the mind as well as for the forest, and sends forth yearly its legion of frontier woodmen and country schoolmasters…” —The Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving

When Washington Irving sat down in 1819 to write his famous short story The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, he was living in the north of England. Ensconced near the eerie landscape of the fog-shrouded Yorkshire moors, Irving was instead inspired by the land of his youth—the rolling hills, rivers, and forests of New York’s Hudson River Valley. Influenced by the romantic movement’s embrace of the natural and supernatural world, Irving’s tale imbued the Hudson Valley with a sense of mystery and magic.

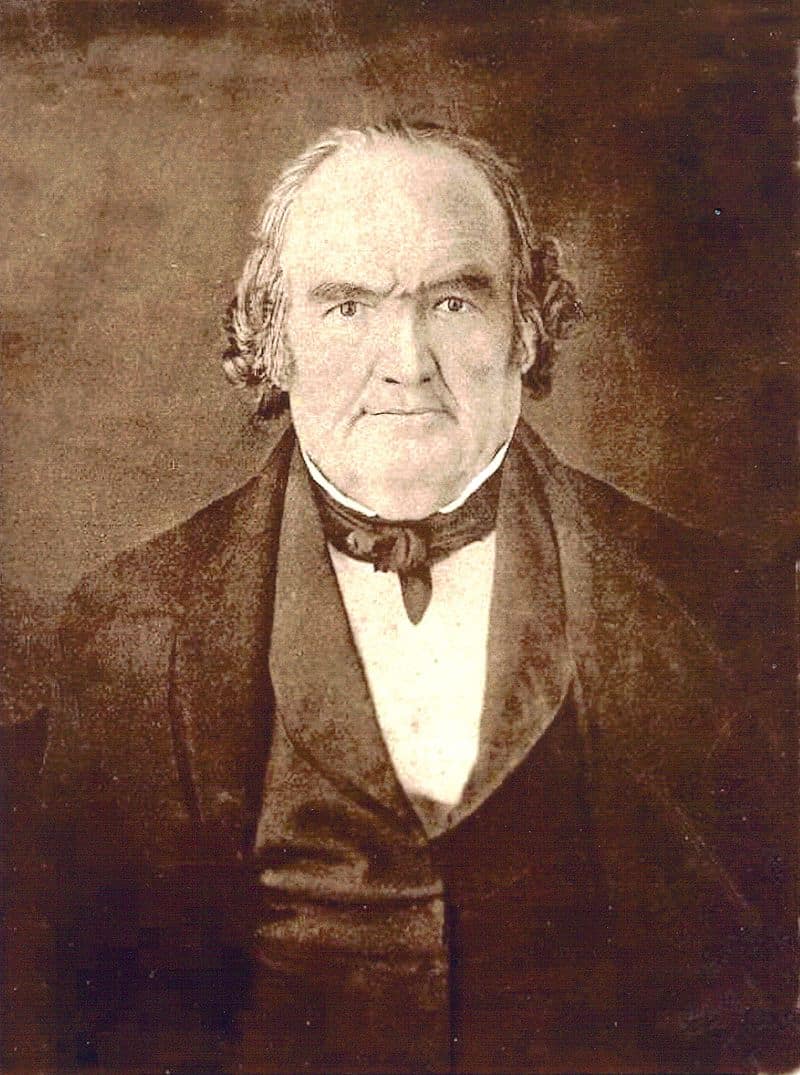

It was in Kinderhook, NY, ten years earlier that the young writer met the man upon whom he would base the main character of his tale—a young man who, like his protagonist—had left his home in Connecticut to teach the descendants of Dutch settlers in a one-room schoolhouse in NY. It was this man, Jesse Merwin of Milford, who would inspire Washington Irving to write one of America’s most famous and enduring tales.

So, who was Jesse Merwin? If you live in Milford, you have heard the Merwin name before. Besides having an engraved stone on the Memorial Bridge, Merwin Point and Merwin Avenue are both named after Miles Merwin, one of Milford’s earliest settlers. Miles was born in Clewer, Berkshire, England in 1623, and settled in Milford in 1645, where he purchased parcels of land in Woodmont throughout the 1600s. Miles Merwin had at least 13 children from three wives. Miles’ great-great-grandson, Jesse Merwin, was born in Milford in 1782. In the early 1800s, Jesse, his parents, and sibling moved from Milford to a farm in upstate New York near Kinderhook. It was here that Merwin took the job as local schoolmaster and shared a boardinghouse with the young writer and tutor, Washington Irving.

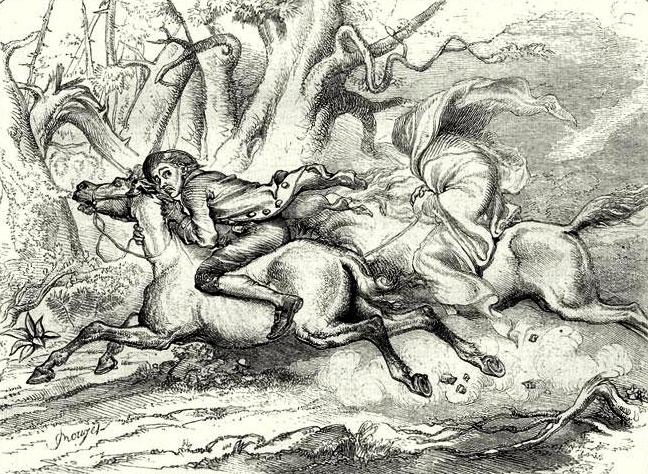

Like most horror stories, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow draws from local legends and has more than its share of truth. Besides the Headless Horseman, which was a legend in the Hudson Valley long before Irving wrote about it, many of the characters made famous by Irving were based on real people he met while in Kinderhook. A man named Brom Van Alstyne became Brom Bones, and the young woman living next to the schoolhouse, Katrina Van Alyn, was the possible inspiration for Katrina Van Tassel.

The character Ichabod Crane is an amalgam of three different people. The name was taken from a real soldier, Colonel Ichabod Crane, whom Irving served with during the war of 1812. But this decorated officer in no way matched either the looks or the meek demeanor of the Ichabod in the story. As for the famous physical description—tall, lanky, huge ears, “long spindle neck,” and “long snipe nose,” Jesse Merwin was not a match. In a letter to Sir Walter Scott, Irving described with amusement a cartoonish-looking Scottish teacher he had met that he called Lockie Longlegs and described him the very same way as in the story.

So how does Jesse become Ichabod Crane?

The Jesse Merwin with whom Irving was friendly does not really match the lazy, cowardly, conniving, superstitious Crane of the story, but family and local lore says there was indeed enough evidence to prove that Merwin was Crane. According to an article published in 1925, Jesse’s grandson, George D. Merwin said, “You recall that Ichabod was lazy; my grandfather wasn’t exactly that, but he disliked school teaching and preferred to talk politics with Irving…he liked to stand around, argue politics and talk a lot.”

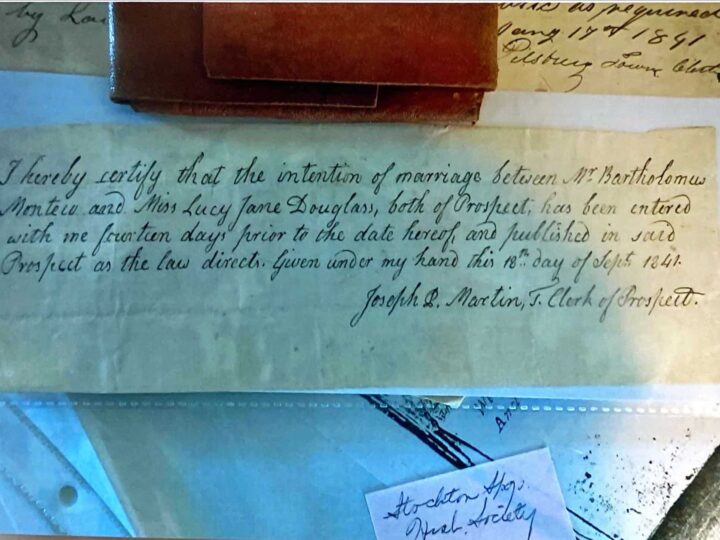

The divide between Merwin and Crane comes together in the book, Legends and Lore of Sleepy Hollow and the Hudson Valley. According to author Jonathan Kruk, Merwin told Irving a story about how, after courting local Dutch girl Jane Van Dyke for years, he was first threatened, and then chased by Brom Van Alstyn posing as the Headless Horseman as a part of a European custom known as a charivari. A custom whereby friends and family of a young woman would encourage or discourage a male suitor by frightening him into either proposing marriage or leaving town, the charivari, according to Kruk, was meant to either “drive a man off or drive him to the alter.” Whether it happened or not, Jesse Merwin married Jane Van Dyke and they had 11 children.

If there was any doubt that Merwin was the basis for Crane, two pieces of evidence put all doubt to rest. In an 1846 letter of introduction, President Martin van Buren, a Kinderhook native, wrote, “…I have known J. Merwin, Esq….for about a 3rd of a century, and believe him to be a man of honor and integrity and that he is the same person celebrated in the writings of the Hon. Washington Irving under the character of Ichabod Crane….” Another piece of evidence was mentioned by van Buren’s great- nephew in a New York Times article in 1898, “…Upon the outside of a letter received from Merwin when they were both old men, Irving endorsed, ‘The original Ichabod Crane.’”

Jesse Merwin stayed in Kinderhook, remained friends with Irving, and enjoyed the “grotesque humor of the portraiture.” He died in 1852 and is buried in Kinderhook, although the Merwin family’s attachment to Milford stayed with them. In the History of Hillsdale, Columbia County NY, author John Francis Collin writes of the Merwin family, “One of their interesting characteristics is their attachment to their old ancestral home, it having remained in the possession of the family 227 years.”

It seems you can take the Merwin out of Milford, chase the Merwin through a forest disguised as a headless ghoul, but you can’t take the Milford out of the Merwin.

chase the Merwin through a forest disguised as a headless ghoul, but you can’t take the Milford out of the Merwin.